Especial Simone Weil (1909-1943) – Bio por Christopher Benfey e vários e-books pra baixar

“Most of human life”, Simone Weil wrote in her essay on The Iliad, “takes place far from hot baths”, but her own discomforts were mainly self-inflicted. She was born in Paris in 1909 into an assimilated, well-to-do Jewish family. (…) Simone Weil was a gifted child, graduating first in her class in philosophy – Simone de Beauvoir was second – at the École Normal Supérieure in 1931. Her mentor was the philosopher Émile Chartier, known as “Alain”, under whose guidance Weil’s political convictions began to surface. Beauvoir recounts her first – and last – conversation with Simone Weil:

“She intrigued me because of her great reputation for inteligence and her bizarre outfits… I don’t know how the conversation got started. She said in piercing tones that only one thing mattered these days: the revolution that would feed all the starving people on the earth. I retorted, no less adamantly, that the problem was not to make men happy, but to help them find a meaning in their existence. She glared at me and said, “It’s clear you’ve never gone hungry.” Our relations ended right there.

Simone Weil had never gone hungry either, but during the mid-1930s she began to seek opportunities to experience the suffering of others. During 1934-1935 she took a break from her teaching to work on the assembly line at a Renault factory. Two years later she was in Spain, enlisting in a workers’ brigade against Franco’s forces… Weil’s experiences in the Renault factory and in Spain confirmed her growing convictions regarding the dehumanizing effects of modern industrialism and war. She traced these tendencies back to the ancient Romans who, in her view, established a mechanistic regime based on brute force. In several powerful essays written during the mid-1930s, she condemned the Romans and argued that Napoleon and Hitler were their imperial successors.

In a letter to propaganda minister Giraudoux, she protested his defense of French colonial policy: “And how can it be said that we brought culture to the Arabs when it was they who preserved the traditions of Greece for us through the Middle Ages?”

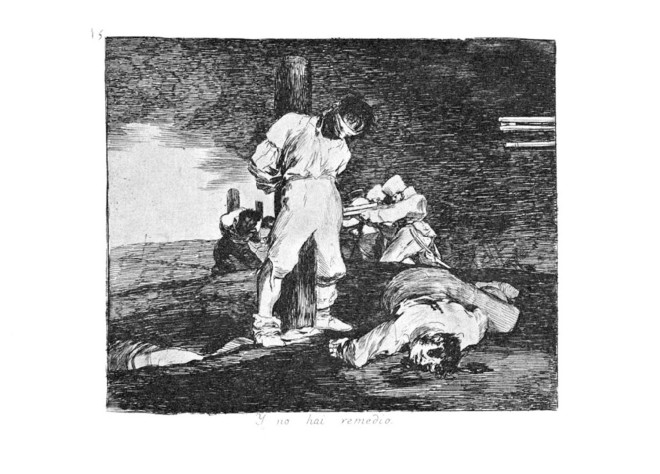

Francisco Goya, Disasters of War (series)

Weil was deeply moved by Goya’s series of etchings The Disasters of War. “It arouses”, she wrote, “an equal degree of horror and admiration.” During the summer of 1939, she renewed her admiration for the artist with repeated visits to the great Goya exhibition at the Museum of Art in Geneva. The exhibition closed on August 31, the day before Germany invaded Poland. The “disasters” Goya depicted – graphic scenes of torture, rape, mutilated corpses, firing squads, mass burials – were carried out by Napoleon’s troops in their invasion and occupation of Spain between 1808 and 1814. Goya claimed to have witnessed many of these atrocities and portrayed them with dispassionate objectivity. (…) Goya’s anonymous scenes of mayhem are typical “products” – as Stephen Crane expressed it in The Red Badge Of Courage – of the machinery of war. And this is how Simone Weil (whether drawing inspiration or confirmation from Goya) read the Iliad, as a disconnected series of “disasters of war”, without narrative or comprehensive meaning beyond the dehumanizing operations of force.

Simone Weil died on August 24, 1943, in a sanitorium in Kent, having deliberately restricted her intake of food to the rations inflicted on her compatriots in occupied France.

CHRISTOPHER BENFEY

In: War and Iliad, by Simone Weil (1909-1943)

and Rachel Bespaloff (1895-1949)

New York Review Books / Classics, 2005

SIMONE WEIL:

SOME OF HER BOOKS

FOR DOWNLOAD

(FREE / PDF)

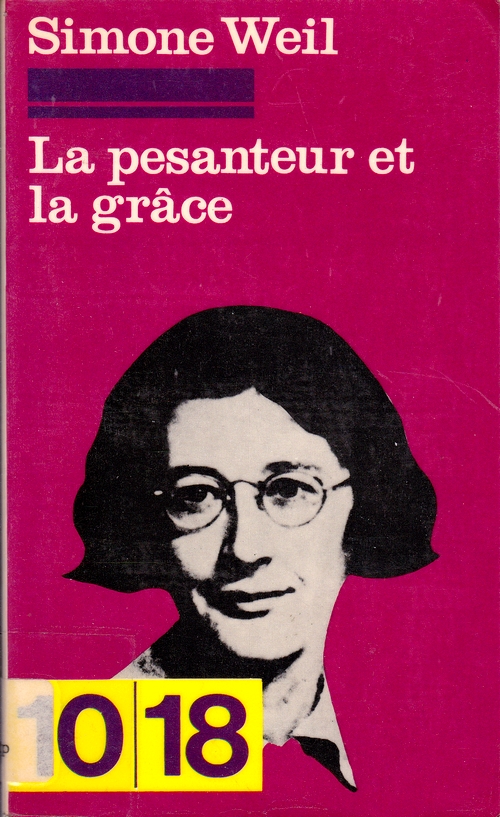

GRAVITY AND GRACE

http://libgen.org/book/index.php?md5=8094BA2655506758EDFC0EECCA769DE4&open=0

Gravity and Grace was the first ever publication by the remarkable thinker and activist, Simone Weil. In it Gustave Thibon, the farmer to whom she had entrusted her notebooks before her untimely death, compiled in one remarkable volume a compendium of her writings that have become a source of spiritual guidance and wisdom for countless individuals. On the fiftieth anniversary of the first English edition – by Routledge & Kegan Paul in 1952 – this Routledge Classics edition offers English readers the complete text of this landmark work for the first time ever, by incorporating a specially commissioned translation of the controversial chapter on Israel. Also previously untranslated is Gustave Thibon’s postscript of 1990, which reminds us how privileged we are to be able to read a work which offers each reader such ‘light for the spirit and nourishment for the soul’. This is a book that no one with a serious interest in the spiritual life can afford to be without.

* * * * *

AN ANTHOPOLY BY PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

http://libgen.org/book/index.php?md5=fa58669d0b9989808e9ebb2f2cd7cd25&open=0

Simone Weil was one of the foremost thinkers of the twentieth century: a philosopher, theologian, critic, sociologist and political activist. This anthology spans the wide range of her thought, and includes an extract from her best-known work ‘The Need for Roots’, exploring the ways in which modern society fails the human soul; her thoughts on the misuse of language by those in power; and the essay ‘Human Personality’, a late, beautiful reflection on the rights and responsibilities of every individual. All are marked by the unique combination of literary eloquence and moral perspicacity that characterised Weil’s ideas and inspired a generation of thinkers and writers both in and outside her native France.

* * * *

LECTURES ON PHILOSOPHY

http://libgen.org/book/index.php?md5=F6AE60C55EA0E505FA6738BE0751DBED&open=0

* * * * *

OPRESSION AND LIBERTY (ROUTLEDGE CLASSICS)

http://libgen.org/get?md5=482BD2760CB7DE6E49CF1252244C2ABE&open=0

The remarkable French thinker Simone Weil is one of the leading intellectual and spiritual figures of the twentieth century. A legendary essayist, political philosopher and member of the French resistance, her literary output belied her tragically short life. Most of her work was published posthumously, to widespread acclaim. Always concerned with the nature of individual freedom, Weil explores in Oppression and Liberty its political and social implications. Analysing the causes of oppression, its mechanisms and forms, she questions revolutionary responses and presents a prophetic view of a way forward. If, as she noted elsewhere, ‘the future is made of the same stuff as the present’, then there will always be a need to continue to listen to Simone Weil.

Publicado em: 08/02/14

De autoria: casadevidro247